by William | May 6, 2020 | Passive House, Small Footprint

Dear Readers,

William and I had the opportunity to listen in on a webinar provided by the Passive House Institute of the United States (PHIUS) on limiting embodied carbon in buildings: “Spaghetti Carbon-Era: Disentangling Operational and Embodied Carbon.” Admittedly, I just got the pun of the title…which is all the more humorous if you were to have seen their intro presenting page being that of pasta in a white sauce with bacon.

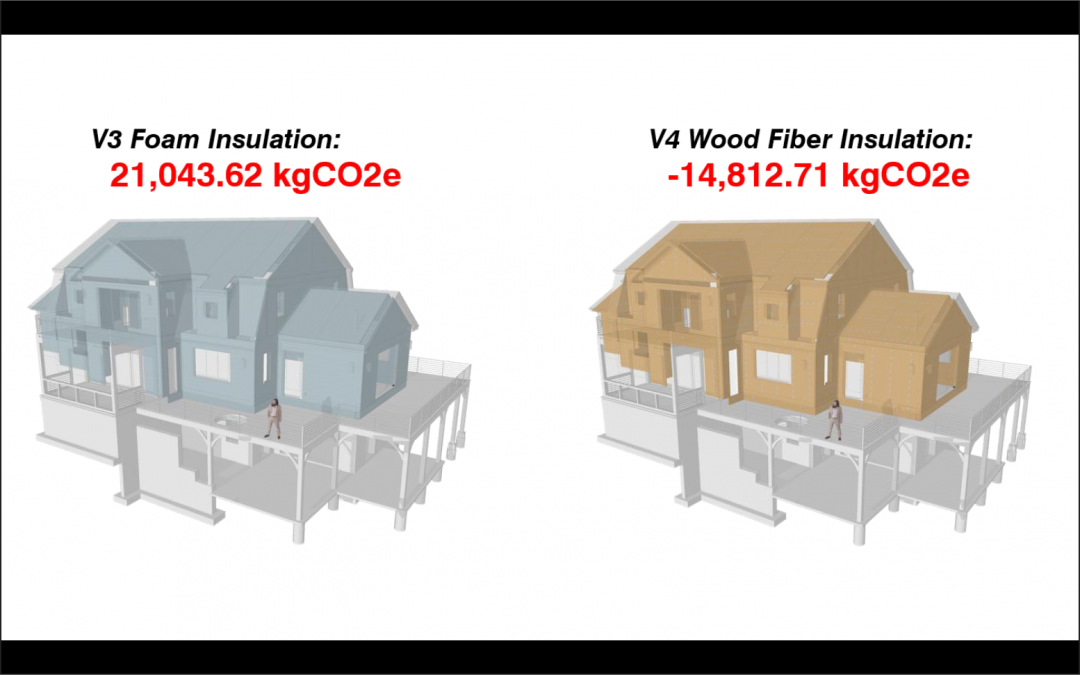

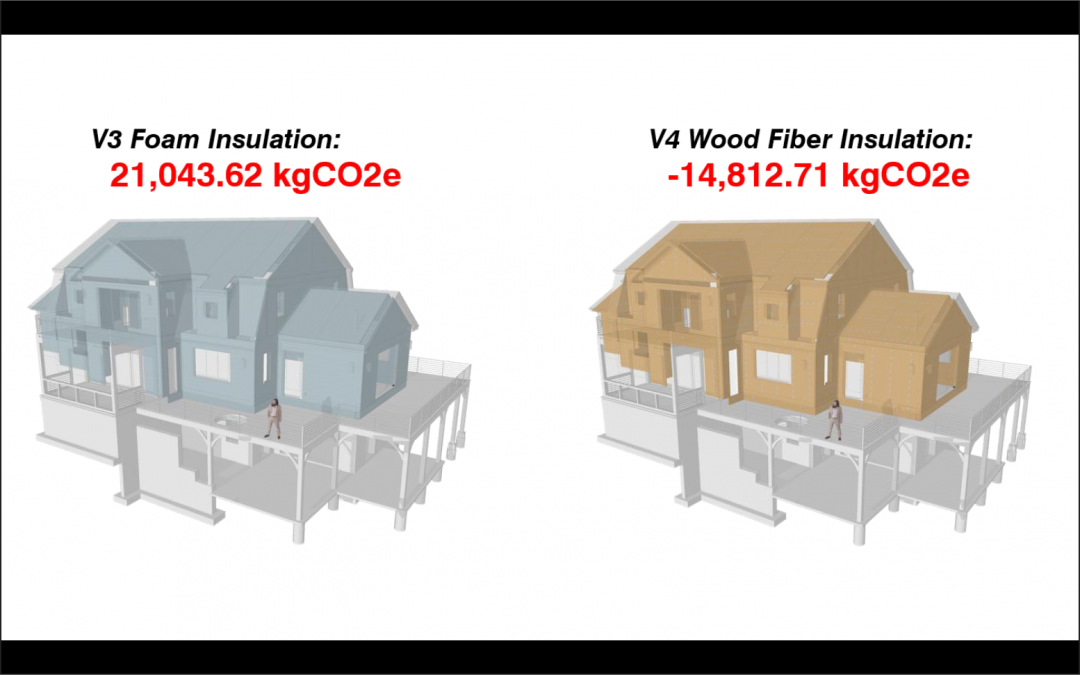

This seminar was very helpful in reiterating the importance of taking a holistically sustainable approach in home building and living. Not only should the home be environmentally friendly and energy efficient during its usage, but also in its construction and sourcing of materials. The ‘environmentally friendliness’ here is measured by the amount of carbon a home is responsible for emitting. PHIUS standards make a home accountable for its carbon footprint in its operation alone: as in, how much energy the home needs to function once it is already built. This they call “operational carbon” or, “OCO2e.” In the webinar, they expressed that the home has an even larger carbon footprint when its “embodied carbon” or, “ECO2e” is taken into account. Embodied carbon is the amount of carbon that is emitted in the overall construction of the home: from the harvesting, manufacturing, and transportation processes of all of the home’s required building materials. That pink fluffy fiberglass insulation and wooden studs and concrete foundation and drywall has to be made out of something and transported from somewhere…all of the materials have their own carbon footprints which then contribute to the home’s overall embodied carbon.

Two of the presenters, Ilka Cassidy and Steve Hessler, founded a business called “Holzraum System, LLC.” Within their business, they did their own study of how much of a home’s carbon footprint is operational and how much of it is embodied. They used five different homes as case studies.

Home One: built to meet 2009 building code

Home Two: built to meet 2009 building code with high performance systems

Home Three: built to meet Passive House standards, but with a high usage of foam

Home Four: built to meet Passive House standards, but with a low usage of foam

Home Five: built to meet Passive House standards, but with no foam.

by William | Apr 29, 2020 | Small Footprint

Dear Readers,

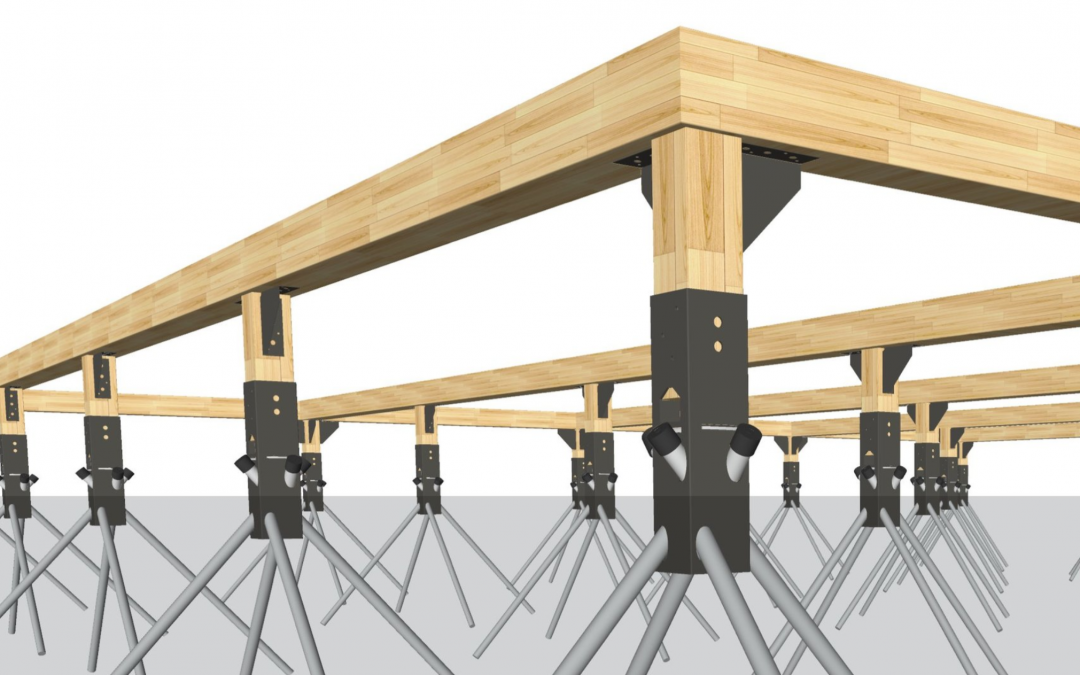

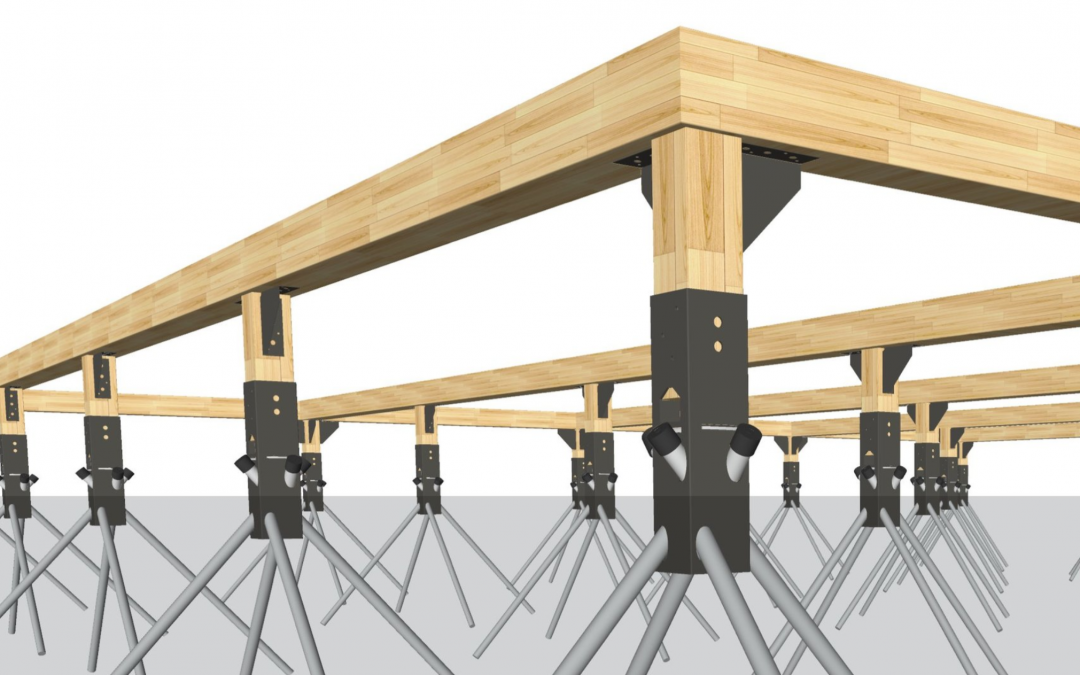

The purpose of this blog is to share some of my own understandings and primary research on pin foundations. The information is useful for a foundational knowledge of how to build a house.

What is the purpose of a foundation?

The three most important functions of a foundation are to be load bearing, act as an anchor, and isolate the home from ground moisture.

Load Bearing: Through the foundation, the weight of the home is transferred from the structure to the ground. The foundation must be able to bear ‘dead’ and ‘live’ loads. ‘Dead’ load is the constant weight of the home structure itself, it never changes. ‘Live’ load varies according to the amount of people, things, or snow in or on the house at any given time.

Anchor: A foundation should act as an anchor for the home against natural forces. A house bolted, or connected, to its foundation is less likely to be swept away by tornadoes or floods, or destroyed by earthquakes.

Isolate: The foundation should isolate the home from ground moisture. Wood, a common building element, rots faster when it is in direct contact with the earth. So, it is necessary to have a separation between the ground and the wood structure.

Why do William and I want to use a pin foundation?

One of the main reasons we wish to use a pin foundation is to lower our home’s environmental impact. Concrete, a typical building material for foundations, has a high output of CO2 and a high consumption of fossil fuels in its manufacturing, transportation, and construction. The laying of a concrete foundation is also a time consuming, physically demanding, and environmentally disruptive process. It can contribute to soil erosion and water pollution, to name a few of the concerns.

by William | Apr 15, 2020 | Small Footprint

Dear Readers,

Before we begin, here are a few key terms…

Cross Laminated Timber (CLT): several layers of lumber boards stacked crosswise and glued (or through other means of attachment) together to form sturdy, thick, structural panels.

Sequester: to take ‘hold’ of. For example, trees have the ability to ‘sequester’ carbon as they grow, and release oxygen. Even if a tree is cut down, it still continues to ‘sequester’ that carbon. Once it is burned or it starts to decompose, it no longer ‘sequesters’ the carbon, and instead releases it into the atmosphere.

Sustainable: Relative.

Again, here is ‘sustainable’ being thrown around like a hot potato. When I first started researching for this blog, I self-defined the ‘sustainability of CLT’ as such: “If CLT continues to gain popularity as a construction material, will forests’ health then be put into jeopardy?” If I found the answer to this question to be, “no, forest health will not be affected if CLT continues to rise in fame” then CLT was, to me, considered to be ‘sustainable’.