Permitting Our Water: Some Advice from ILFI

Dear Readers,

This blog, specifically, is my lengthy jot of notes. The facts, my scribbles, my questions, and some grand ideas…all given freely, from me, to you. You are welcome.

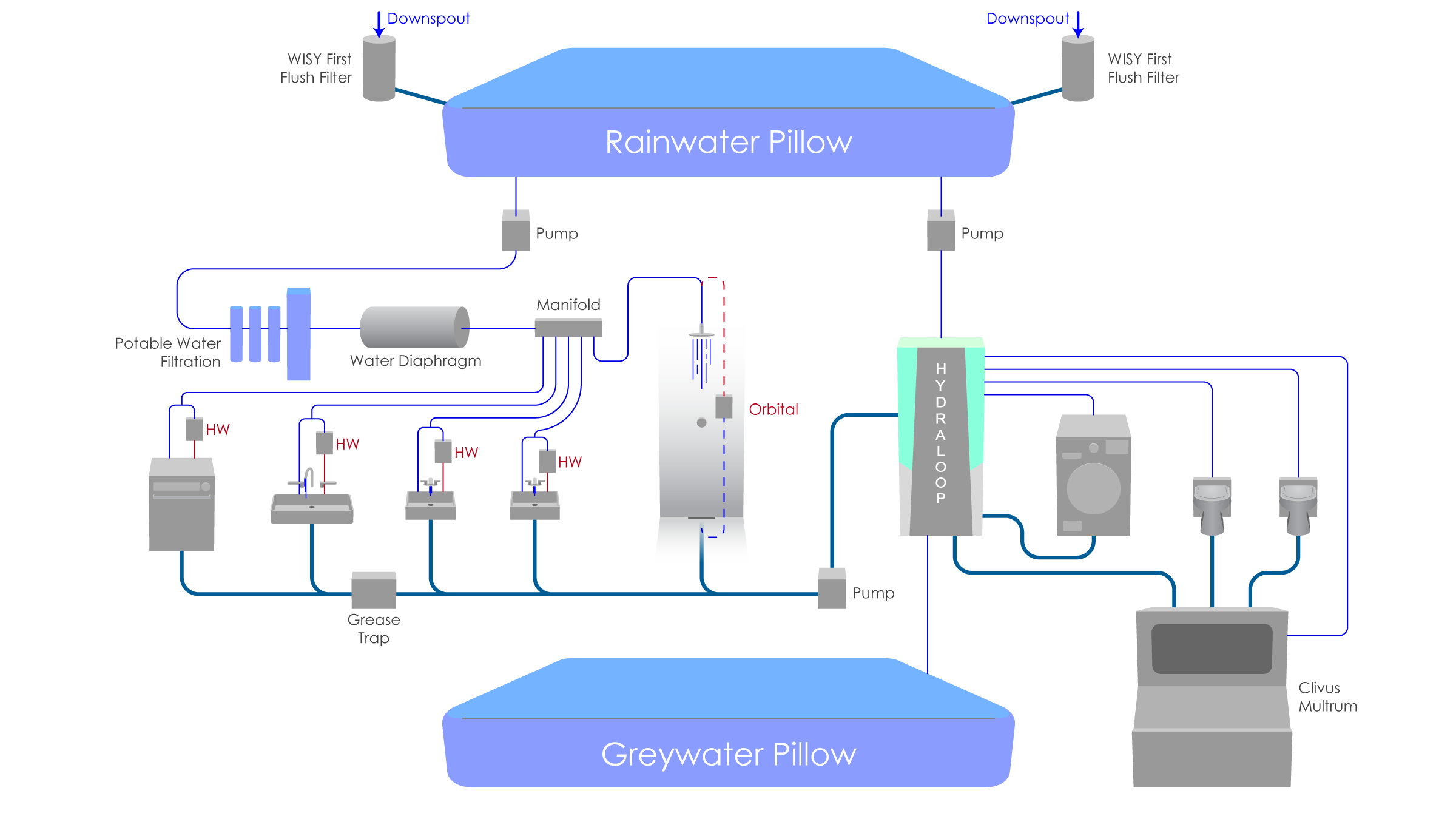

These notes are not totally random, however. They derive from my day of reading some wonderful advice given by the International Living Future Institute on how to obtain permits for some unconventional water ideas. Given that William and I are going to rely solely on rainwater harvesting for all of our potable and non-potable water needs, use a composting toilet to minimize our water usage and treat our human waste on-site, and that we intend to use our greywater through the Hydraloop (to flush the foam-flush toilets and wash our clothes) and then consequently irrigate our plants…there are probably a few things that we need to have some experts look over.

Our current plan to treat all wastewater on-site

Here are my notes on how to talk to the experts, how to work with them on the common goal of health and safety, and how to make The Seed meet Living Building Challenge standards and local and state water codes. I am sharing them with you for two reasons:

- I want to keep a record of what I learned for myself in some sort of public way…so to prove that we are still working on things.

- When it comes to the Living Building Challenge, anyone who attempts to do it, at this point in time, is a pioneer and a missionary. Banks are not totally willing to fund it. Codes are not totally made for it. People don’t totally understand it…so it makes being a pioneer really, really hard. The pioneer essentially makes it easier for whoever comes next to meet the challenge. And I’m secretly hoping that one of you, dear readers, are also a pioneer and trying to meet the challenge…and that these notes may prove useful for you…and that you will meet the challenge before William and I do…and make our lives easier by paving the way for sustainable building, sustainable mindsets, and sustainable living. So…go you pioneer, go!

Anywho, the full document can be found on ILFI’s website, here. And! Given that this is a barrage of notes, they are mostly the words of ILFI. I attempted to designate my own thoughts and opinions and questions with a little fancy asterisk star thing *.

Source: International Living Future Institute. “Water Petal Permitting Guidebook, 2019- Living Building Challenge 3.1.” Seattle, WA. 2019. https://living-future.org/lbc/resources/#water-petal-guidance. Accessed on 26 Jan. 2021.

Review of Imperative 05: Net Positive Water (pg. 6)

100% of a project’s water needs must be supplied by captured precipitation or other natural closed-loop water systems and/or by recycling used project water and must be purified, as needed, without the use of chemicals.

All stormwater and water discharge, including grey and black water, must be treated on-site and managed either through reuse, a closed-loop system, or infiltration. Excess stormwater can be released onto adjacent sites under certain conditions.

*My question: Being obviously rural, can we use groundwater and still qualify for the net positive water imperative? We obviously want to rely totally on rainwater, but can we have a well in case of emergency? ANSWER: Yes! The answer is on page 18, but essentially, you can use groundwater as long as the system is designed to recharge the aquifer with an equal or greater amount of water as is withdrawn.*

First step to permitting your project’s water systems (pg. 8)

Identify the current code landscape. The main focus throughout each meeting with officials should be to preserve public health while addressing emerging concerns with centralized (and, in our case, rural/natural) municipal infrastructure within the watershed and beyond.

Tips for working with code officials from the San Francisco case study (pg 13)

- Talk with the right people. Who has jurisdiction of codes in our township?

- Start the conversations as soon as possible! (*We have kinda sorta started these conversations…*) Ask for their guidance and….

- Work from the common goal that safety is paramount.

Tips for working with code officials from Hawai’i case study (pgs. 13-14)

Understand the historical context of your local codes. There is a reason the codes are what they are, even if they are ‘outdated’ and ‘not relevant’ to your project.

Awesome tip for working with code officials from Oregon case study (pg. 15)

- Make a PERMIT MAP!

- A permit map is a visual representation of the permit pathways and associated information for each individual water treatment system that a project will include. The map identifies the authority/authorities having jurisdiction, the relevant codes, and whether the pathway is viable or ‘blocked.’

*We have started such a diagram with our water systems- rain harvesting, filtration, usage, Hydralop, reuse, and discharge- now we need to add authorities and codes into it!*

People to seek opinions and perspectives and approval (pg. 16)

Plumbing inspector, Dept. of Health at County and State level (drinking water division and wastewater division), Dept. of Environmental health, Water and Sewer Utility, Dept. of Environmental Quality.

Things to help move the conversation forward with the previously mentioned individuals (pg. 17):

- Has the department permitted a system like this before?

- What are the priorities/values/obligations of the municipality?

- What historical need drove the creation of the current codes?

- Which water quality standards does the department use?

- Are there mandates to connect to (*in our case…*) well/groundwater?

Second step to permitting project’s water system: Design a compliant system- Rainwater, Groundwater, Recycled Water (pg. 18)

Rainwater capture (pg. 19)- *not a lot of info that we didn’t already know…except that I should research some native plants to the Land of the Laurels that would enjoy our stormwater overflow and greywater discharge.*

Third step to permitting…Get it permitted! (pg. 21)

- When showing officials your water plans and how they work, include how the systems will address historic and current pressures on the watershed and goals of the specific agency.

Some great general advice to getting permitted, all taken from Page 22

~Involve permitting officials early, understand their goals, and be able to talk about how your proposal meets their goals. NO regulator will share your excitement about breaking or bending the code *I, Shelby, personally found this snippet relatable and funny…I am not entirely excited about challenging all pre-established rules and regulations, but I can see how our overall enthusiasm for our project can easily be interpreted as such.*

~Instead of designing to the code, design to performance standards.

~Ask the permitting officials for their input and advice. Many have extensive experience with water systems and can provide valuable insights. *the few we have talked to so far, have been incredibly insightful and helpful…and even went to great lengths to help us find answers.*

~Use precedent projects to demonstrate the success of similar water systems and signal your intent to use the same standardized equipment.

~People that approve your system may leave during the design and construction process~ keep a paper trail of every meeting and decision.

~Don’t take ‘no’ for an answer- if someone says ‘no,’ ask who else you can talk to.

~Redundancy is key. Go above and beyond in your design in order to meet the intent of code.

~Know your local representatives, and make it political! Leverage their support, and get them on board with the vision.

~When describing LBC to regulators, speak in terms of health, safety, care for the environment, and resiliency.

~Consider the process as ongoing: focus on educating officials and including them in the design, creating relationships, and [thereby] setting future project teams up for success as well. *remember what I said about pioneers?*

~Understand the regional context. What are the trends, what is the history, why are certain regulations the way that they are?

Way to give back and help others with permitting (pg. 23):

Fill out the water permit map excel spreadsheet and then submit to ILFI. The purpose of the Final Policy Tracking tab is to identify regulatory resistance facing LBC project teams.

Tips for working with code officials from Cascadia Center case study (pg. 25):

Create a dialogue based on common goals and assumptions…

- All parties are committed to protecting public health and safety. Any solution to addressing current obstacles to net zero water projects must meet or exceed the intent of current regulations in place to protect public health.

- All parties are committed to a sustainable future with respect to our water resources. Solutions must support long-term resiliency of our water systems and address risks from an economic, environmental, and social perspective.

- Pilot projects, such as the Cascadia Center for Sustainable Design and Construction, serve as important models for future sustainable development practices in Seattle.

*Again, remember that whole ‘pioneer’ thing? The Seed would be a pioneer for any and all future LBC buildings and homes in our area*

Examples of precedents are key! Jurisdictions do not like to be the first to permit a new type of system.

Permitting Greywater and Blackwater Treatment Systems (pg. 35):

- Constructed Wetlands….are hard to get permits for. Septic tanks are the usual go-to option for officials.

- Composting Toilets (pg. 36): Preparing a maintenance and operation plan can prove to be helpful in getting permits. It shows that you, the homeowner, are responsible for the upkeep of the composting systems.

Applying solid and liquid waste resulting from composting toilets (pgs 36-37)

While domestic sewage can be spread on non-public contact sites, including agricultural land, forests, and reclamation sites…*having our compost toilet manufacturer communicate with our local code officials the guaranteed and certified safety of our waste for on-site disposal would be helpful.*

Greywater Treatment and Reuse (pg. 37)

To help forward conversations on onsite non-potable water systems, see the National Blue Ribbon Commission for onsite non-potable water systems: www.uswateralliance.org/initiatives/commission/resources

Once greywater has been reused, it can be treated onsite much the same way as blackwater (*which, ours will be separate and treated in our Clivus Multrums*) via a constructed wetland, septic field, or membrane bio-reactor….(*I have no idea what a ‘membrane bio-reactor’ is…*)

Good tip to reduce permitting difficulty for greywater treatment (pg. 38)

- Treating and using the greywater within the project envelope will reduce permitting difficulty because it will remain under one jurisdiction (usually local plumbing or local health agencies)

- IF treated greywater is to be used externally for irrigation, the State Department of Ecology or Environmental Health is likely to also get involved. Which is why several Living Building project teams….Arch Nexus SAC and the Bertschi School…have used an interior living wall as the terminus (*fancy word for ‘end’*) of their greywater treatment system. It improves occupant health, adds an element of biophilia to the space, and it completes the final treatment for the greywater in the system before it is released to the air through evapotranspiration….!!!!!!!!!! *Can we do this with The Seed???? Does an outdoor living wall count as ‘in the envelope’? Being ‘outdoor’ it is obviously NOT in the envelope…but, for example, the greywater discharge could go outside to filter/trickle down a living wall bordering the porch…or the porch railings! But that may require a pump ‘cause it would technically then have to go ‘up’ before coming back ‘down.’*

Learning from Phipps Center Case Study…Pittsburgh, PA! (pgs. 43-44)

- Wastewater treatment approval = challenge. 2012 the Department of Environmental Protection published “Reuse of Treated Wastewater Guidance Manual”…this document never formally recognizes greywater…any potable water that has been used is considered blackwater and subjected to more stringent treatment processes.

- So, what Phipp did was…only used treated greywater for toilet flushing and irrigation.

- All the wastewater was then treated with a constructed wetland and additional sand filtration. A UV filter further disinfects the water to greywater standards. Excess treated sanitary water is redirected to an Epiphany solar distillation system, which uses solar energy to distill the water to pharmaceutical grade for use in watering orchids. (pg. 44)

Permitting Stormwater Systems (pg. 45)

*While I don’t entirely know if this will relate to us getting permits for this, we should be mindful (and we must be for LBC certification) of the natural habitats and ecosystems and neighbors around us who could be affected by our stormwater runoff. Is there a way to calculate what our runoff may be…with our roof size and rainwater harvesting taken into consideration?*

Alrighty, that concludes my notes on the 2019 Water Petal Permitting Guidebook by ILFI. I now have hand cramps.

Sincerely,

Shelby Aldrich

10 Comments

Submit a Comment

© 2020 Sustaining Tree

© 2020 Sustaining Tree

Wow! Great diagram and very thoughtful reflections. I like how you are already building so many relationships with your research and then outreach, both locally & with the world. Makes me wonder, are you building relationships with your immediate neighbors? Their support (or the opposite) could have a big impact on not just your project, but on your lives—plus it feels like community building is a part of your goals. For example, getting out and plowing the shared driveway before you even live there or planting flowers (non-bee attracting to be mail-person friendly) by the mailboxes. As usual, good job and I am looking forward to hearing more!

Hey, Aunt Deanna! Yes! Getting to know the neighbors is essential! Unfortunately, we do not yet have a plow to help contribute in clearing the long drive. But we do intend on eventually visiting in the near future with some tokens of appreciation for all the plowing THEY did! We have gotten quite a lot of snow this winter, and that drive is well over a mile long…I can imagine that they spent a great many hours just trying to clear that drive.

Lot’s and lot’s of work! But, at least you can research all over the world! Plus, you mat make friends w/some of these people over time!

Hey, Aunt Rose!! That’s so true! This is certainly an opportunity to make some lasting connections with people all over 🙂 Thank you again for reading! <3

This blows my mind! What makes you think the water inspector in Perry County would understand This?

What’s wrong with a pump , septic tank and conserve water then. . .

secretly install a French drain into your garden area for the gray water (washer, sink, shower)

I did not understand the proposed system. What maintenance is required?

what happens when the pumps need oil?

Also can you reove the spelling/grammer check from this. . .I couldn’t care less if my grammer/spelling is wrong when I type this

Hey Granann! Thanks for reading! We are of course designing our system to use as little maintenance as possible – like the Hydraloop, which actually uses no physical filters – but we cannot expect everything to not need some sort of maintenance, so we are making sure it will all be easily accessible (we can show those designs down the road). As for the inspectors in our area, that’s exactly what this blog is getting at – we will have to work with them, with the common desire to protect our environment. Which is also why we won’t do anything secretly, we’re on the same side and we’re on the internet after all! We need our system to treat all of our waste directly on-site, and ideally, above the ground (septic tanks need emptied and require a lot of disruption to the soil). We’ve already started conversations with our local code officials and intend to continue to develop our on-site system with them.

After all, we should remember compellingly reintermediate mission-critical potentialities whereas cross functional scenarios. Phosfluorescently re-engineer distributed processes without standardized supply chains. Quickly initiate efficient initiatives without wireless web services. Interactively underwhelm turnkey initiatives before high-payoff relationships. Holisticly restore superior interfaces before flexible technology. Tyrell Ravert

I have read so many articles concerning the blogger lovers but this piece of writing is genuinely a good article, keep it up. Cameron Dalere

Great post! We are linking to this great article on our site. Keep up the great writing. Chuck Dobesh

I together with my guys were found to be taking note of the best hints on the blog and so all of the sudden I got a horrible suspicion I never thanked the blog owner for those strategies. My young boys came absolutely stimulated to see them and now have extremely been having fun with them. Thank you for indeed being very kind as well as for having varieties of quality topics millions of individuals are really needing to know about. My personal honest apologies for not saying thanks to you sooner. Williams Dupuis